Vijñānabhairava-tantra, Verse 70 Recalling a sexual encounter

Summary of discussion on Vijnana-bhairava-tantra made by Guru Yogi Matsyendranath and Rev. John Dupuche

The śloka reads as follows:

“O Mistress of the Gods, bliss surges even in the absence of a śakti, through the act of recalling intently the pleasure experienced with a woman, the kissing, the embracing, the clasping.”

लेहनामन्थनाकोटैः स्त्रीसुखस्य भरात्स्मृतेः।

शक्त्यभावेऽपि देवेशि भवेद् आनन्दसम्प्लवः॥ ७०॥

lehanāmanthanākoṭaiḥ strīsukhasya bharāt smṛteḥ |

śaktyabhāve ‘pi deveśi bhaved ānandasamplavaḥ || 70 ||

The operative word is ‘recalling’ (smṛteḥ). It presupposes an earlier experience. It is not fantasizing, or imagining what has not happened. It is not a form of pornography or voyeurism. It is not compensation or make-believe. It is the act of recalling a delightful episode, which did in fact happen.

This recalling is to be distinguished from the karmamudrā in Buddhism, which is the experience of union with a real woman (mudrā), or the jñānamudrā which is the contemplation of womanhood. Note that similar terms, karmadūtī and jñānadūtī, appear in the Āgamarahaysa where the word dūti refers to the sexual partner. Note also that the word dūti is prominent in the description of the Kula Ritual in chapter 29 of Abhinavagupta’s Tantrāloka.

The term sukha forms one item of the pair sukha – duhkha, pleasure – suffering. This reliving of pleasure (sukha) with a woman (strī) leads to the experience of that bliss (ānanda) which is the state of Śiva and Śakti in their 1000 year intercourse (maithuna) (the figure 1000 being code for ‘everlasting’).

Śiva and Śakti, in their eternal union, are the basis of all reality. Everything that exists is the outflow of their sexual intercourse. Therefore the individual man and woman in their joining are expressions of Śiva and Śakti, and are united with all the copulations that occur in every moment, for the whole world is one vast field of love-making. That is why the couple senses such harmony with the whole universe. All mirrors all.

The pleasure was powerful at that time in the past because it was an inkling of the bliss that belongs to Śiva and Śakti in their eternity. The act of remembering returns the practitioner to that moment.

The previous śloka 69 refers to the concluding moment of an actual sexual act, therefore to the sthūla (objective, ‘gross’) level. This śloka 70 is a dhāraṇa at the subtle level based on the power of memory (smṛti). Both lead to the sense of maithuna at the supreme (para) level, since all is derived from para.

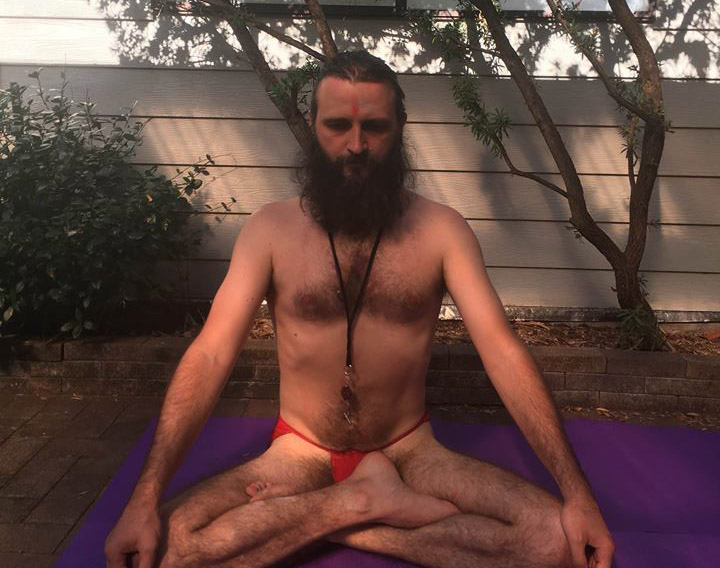

brahmacārī

The question arises then about the brahmacārī who has not experienced pleasure with a woman. Is he excluded from practicing this dhāraṇa. Yes, of course, since he has not had a past sexual encounter. But the sexual encounter of that sort is limited by its very nature. It did not, could not, last. The brahmacārī by contrast, does not seek “the kissing, the embracing, the clasping” (lehanāmanthanākoṭa) as the means to experiencing the eternal union of God and Goddess. Rather, he seeks to experience the supreme (para) divine intercourse from the outset. The desire arises in him for an eternal maithuna, which is found in every circumstance. This is his desire, his intention (samkalpa) from the start.

By a powerful gift of grace he experiences already at the highest level the union of the Divine Couple. He knows he is already Śiva in union with Śakti but also in union with all the śaktis that emanate from her. He experiences the stillness and energy that lies at the very origin of all things. He knows the divine maithuna at the deepest level of consciousness, for that godly sexuality is the heart of reality.

He is inverting the procedure, therefore, not proceeding from the lower to the higher but allowing the higher to inform the lower. As he rests in this state of bliss (ānanda) his whole person, his word, mantra, mind, emotions, feelings, his very body and all its faculties are filled also with the delight (sukha) that is sexual. He knows both the ānanda and the strīsukha. Thus, at every moment, the brahmacārī experiences intercourse ever more frequently, ever more consciously. He has the fullness of sexuality and is united with the whole of the universe. This is described by Abhinavagupta, in Tantrāloka 29.79, as follows:

Moreover, having by his own nature become the sole Lord of the Kula, he should satiate the many śaktis by pairing [with them], he who possesses every form.

Jayaratha, in his commentary on TĀ 29.79 reinforces this statement with a quote

“His śaktis are the whole universe …….”

In Christian terms, the teaching has always been that the truly dedicated virgin, male or female, experiences already both the original and the future state:

For in the Saints who consecrated themselves to Christ

for the sake of the Kingdom of Heaven,

it is right to celebrate the wonders of your providence,

by which you call human nature back to its original holiness

and bring it to experience on this earth

the gifts you promise in the new world to come.

(Roman Missal, ‘Preface of Holy Virgins and Religious’)

This teaching receives a fuller explanation in the light of śloka 70.