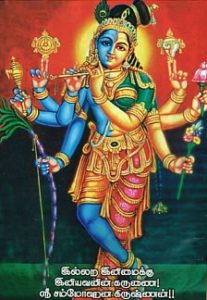

Today is an interesting day, the birthday of Nṛsiṃha, the incarnation of Viṣṇu, and of the Goddess Chinnamastā. According to the Toḍala-tantra, the Ten Mahāvidiyās are associated with the Ten Viṣṇu avatārs.

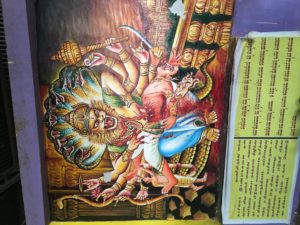

What do the images of Chinnamastā and Nṛsiṃha have in common? According to one legend, Nṛsiṃha came to destroy the demon Hiraṇyakaśipu. Hiraṇyakaśipu, performing austerities, asked Brahmā not to be killed either outdoors or indoors, either on the ground or in the air, either by humans or animals. Then Viṣṇu appeared in the form of a half-man and a half-lion, he killed the demon on the porch of his palace, placing him over his knee. So the demon was killed in a way that he did not expect. There is also a continuation of this story, in which Nṛsiṃha gets drunk on the blood of the killed demon and becomes infected with it. After that, Śiva appears in the form of Śarabheśvara and neutralises the blood of the demon in Nṛsiṃha. Śarabheśvara is depicted not just as a lion, but with wings, i.e. he has a great ability of manifestation in various realms, since he is able to fly through the air. Two Goddesses appear from his wings, one is Pratyaṅgirā and the other is Śūlinī Durgā, both of which are related to the elimination of the negative influence or witchcraft on the practitioner. In fact, Śarabheśvara is nothing more than an enhanced form of Nṛsiṃha. I heard from Indian tantrikas that there are no contradictions here, because Viṣṇu and Śiva are fused in the form of Harihara.

What do the images of Chinnamastā and Nṛsiṃha have in common? According to one legend, Nṛsiṃha came to destroy the demon Hiraṇyakaśipu. Hiraṇyakaśipu, performing austerities, asked Brahmā not to be killed either outdoors or indoors, either on the ground or in the air, either by humans or animals. Then Viṣṇu appeared in the form of a half-man and a half-lion, he killed the demon on the porch of his palace, placing him over his knee. So the demon was killed in a way that he did not expect. There is also a continuation of this story, in which Nṛsiṃha gets drunk on the blood of the killed demon and becomes infected with it. After that, Śiva appears in the form of Śarabheśvara and neutralises the blood of the demon in Nṛsiṃha. Śarabheśvara is depicted not just as a lion, but with wings, i.e. he has a great ability of manifestation in various realms, since he is able to fly through the air. Two Goddesses appear from his wings, one is Pratyaṅgirā and the other is Śūlinī Durgā, both of which are related to the elimination of the negative influence or witchcraft on the practitioner. In fact, Śarabheśvara is nothing more than an enhanced form of Nṛsiṃha. I heard from Indian tantrikas that there are no contradictions here, because Viṣṇu and Śiva are fused in the form of Harihara.

If you look at the image of Chinnamastā, you will see that it stands on Kāma, the God of sex, who is in the intercourse with his companion Rati (Goddess of passion). Thus, Chinnamastā gets energy from passion, but in its essence, this passion is also self-transformation or sublimation. Chinnamastā chopped off her own head and holds it in her hand, while her head drinks a stream of blood from the body. Two other streams are drunk by her two companions. This is a symbol of the three channels, where Chinnamastā herself symbolises suṣumṇā and the other two Goddesses – the channels iḍā and piṅgala. In other words, Chinnamastā is a certain single reality that is present in all channels, in the power of passion and creation. In fact, it is a single indestructible force within every living form. Her mantra is the same as the Vajravārāhī mantra in Buddhism, who is also known there as the Goddess Khecharī (mudrā) of white color. The name Chinnamastā in the mantra is “Vajravairocanī” (‘the shining lightning’), and the term vajra could also mean “indestructibility”.

From my experience of worshiping Chinnamastā, I can say that this form is associated with a deep comprehension of one element or aspect of self, through which it is possible to penetrate into all others. You kind of unite them and go beyond them. In yoga, for example, you exhale smoothly (rechaka) and automatically comprehend the essence of the correct inhalation (pūraka). Through both of them you comprehend the essence of the retention (kumbhaka). Kumbhaka – from the root कुम्ब् / kumb ( something which encompasses, embodies in itself). Therefore, a vessel is often a symbol of female genitals (yonī), from the root यु / yu, – something which connects, forms and holds in itself. Yonī could also mean something that is associated with various forms of birth, all creation comes from it, all forms of life, they dissolve in it. Kumbha or a vessel is a symbol of the body, both individual and the body of the universe, all life (amṛta) and the whole universe is in it. A vessel is a symbol of the unity of external and internal space (vyoman), the void inside and outside a vessel is one in its essence. Therefore, there is one single reality in all our bodies. We could say that these are parts: inhalation, exhalation, retention, like other parts of yoga, besides prāṇāyāma, āsana, pratyāhāra, dhāraṇā, yama, niyama, etc. All of them are one single sādhanā, one yoga, like other yogas (rāja, karma, jñāna, laya). Unfortunately, people have separated all these methods now, although they have one goal and one reality. Once you comprehend one aspect well, you automatically come to the comprehension of its inextricable connection with all others. Chinnamastā is a very paradoxical symbol, it is a symbol of cutting off all worldly things and at the same time it is a symbol of presence in everything. It is the transcendental, indestructible, radiant emptiness that generates an abundance of life forms and is present in each such form. Surely, she is associated with the complete absence of oneself in something, but also with the complete presence of oneself there. Chinnamastā is a symbol of spiritual death in which there is no conditioning by births, she is also a symbol of the fullness of life and the infinite wealth of life. Fear of death and fear of life are usually related. A yogi is one who dies for the world and through this death he is resurrected to a new vision of life in all its beauty and fullness. In this regard, Chinnamastā is a part of the Kālī pantheon (Kālī–kūla), because Kālī is connected with time, which is divided into parts, into segments. The term Kālī is feminine from kāla (‘time’), which is masculine. It comes from the root कल् (kal), which is the first gaṇa (group of roots) of ten in Pāṇini, and means सङ्ख्यान (saṅkhyāna – “to count”) , and कला (kalā) is from the same root – “a part of something general, art, etc.” She teaches to control prāṇa, and through the management of prāṇa leads to going beyond time or death.